Waterfront Histories: Historic images

A selection of historical photos and stories of Black, Indigenous, and Asian-American people

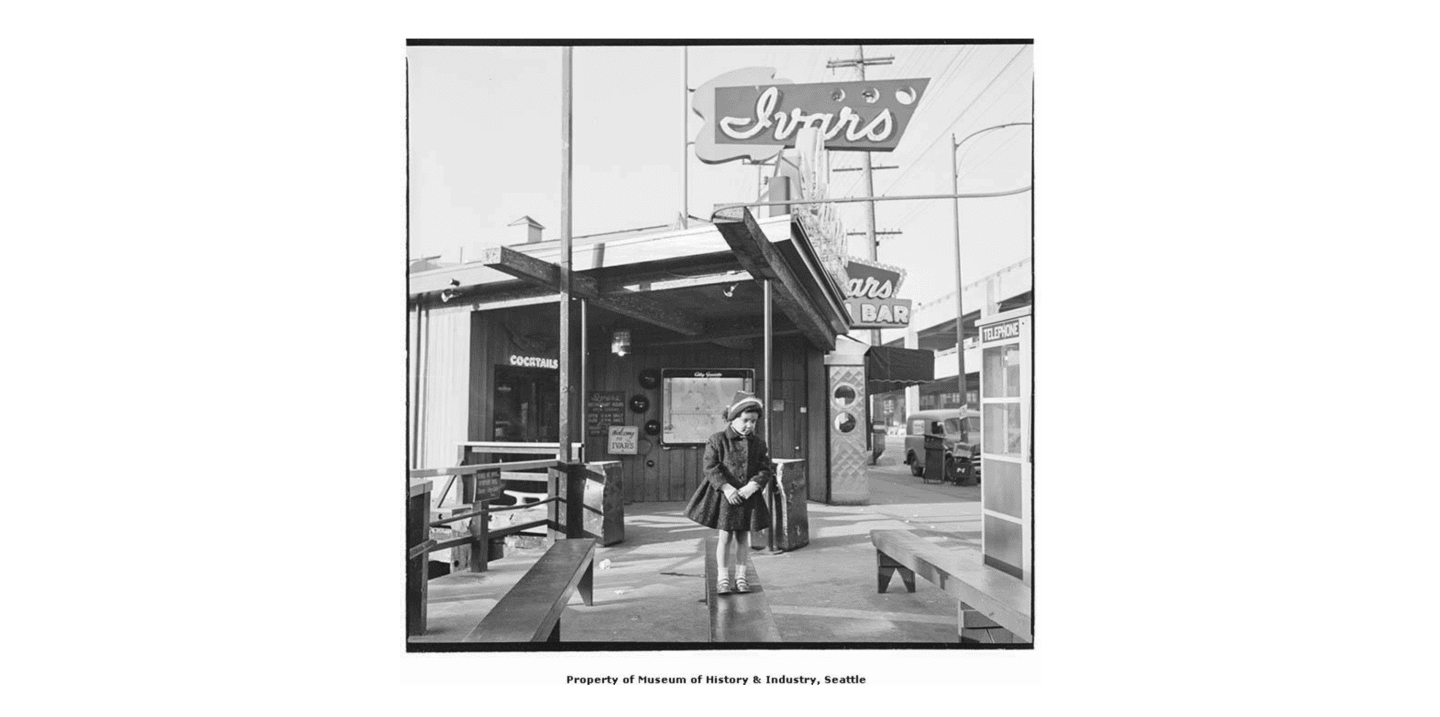

Cheryl Inez Smith,

This nostalgic image of Cheryl Inez Smith at Ivar’s Fish Bar was taken in 1953 by her father, Albert Smith, Sr. Cheryl is quietly gazing downward standing atop a bench adjacent to the fish bar at a tranquil Pier 54 with the now demolished Alaskan Way Viaduct in the background. The photo depicts a calm afternoon out and about with her family. What it does not describe is the tumultuous and discriminatory past of the waterfront docks at the turn of the 20th century when, for the first time in Seattle history, Blacks were hired in 1916 to replace the middle-class white strikers of the International Longshoremen’s Association. Seattle’s Black population grew from 400 in 1900 to 2,200 by 1920. The Black community formed its relationship with the waterfront out of struggle, acceptance, and renewal.

The past is complicated, and the present sits at a restorative juncture that not so quietly gazes toward embracing a shared historical footprint placed intentionally in the future.

Description provided by Stephanie Johnson-Toliver, President of The Black Heritage Society of Washington State, Inc. Seattle, WA | www.bhswa.org Cheryl Inez Smith, Seattle, 1953 Photo credit: MOHAI-Al Smith Collection

On March 30, 1942, more than 200 Japanese Americans were ordered to leave Bainbridge Island. This group was the first of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their West Coast homes and placed in concentration camps during World War II under Executive Order 9066. During this time, Japanese Americans could only bring with them whatever they could carry, and everything else was left behind.

This photo was taken at the Seattle waterfront and shows Japanese Americans – who had arrived in Seattle from Bainbridge Island via the ferry (the nearby ferry terminal still stands to this day) – boarding a train, while crowds watch from the Marion Street overpass. The incarcerees traveled by train to the Manzanar concentration camp which was located in the California desert near Death Valley, and some were later transferred to the Minidoka camp in southern Idaho. These were two of 10 large camps in which Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II.

This is only one facet of the Japanese American story. To learn more about the Japanese American incarceration, the rich history of Japanese Americans in the Pacific Northwest as well as the history, cultures, and art of Asian Pacific Americans more broadly, visit the Wing Luke Museum located in the Chinatown-International District.

Description provided by Jessica Rubenacker, Wing Luke Museum Exhibit Director. wingluke.org

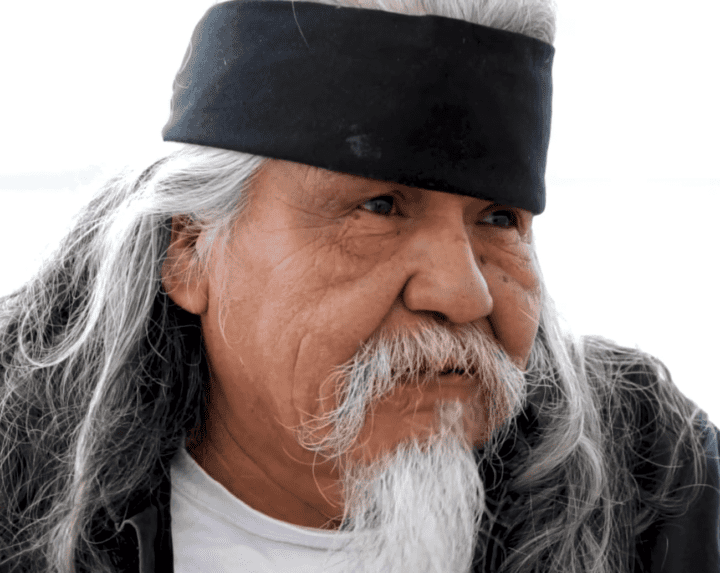

Puget Sound Salish Tribes have inhabited this area for thousands of years. An abundance of natural resources and efficient technologies for harvesting and preserving food enabled them to develop rich cultural and spiritual life ways. In 1855, the Treaty of Point Elliott was signed with more than 20 tribes in the Puget Sound region, creating reservations as permanent homes for the tribal populace. The Suquamish Tribe was assigned to the area around their mother village of Old Man House on the Kitsap Peninsula, where the Port Madison Indian Reservation was established. Chief Seattle signed the treaty as a representative of both the Suquamish and Duwamish Tribes and some Duwamish families moved to the Port Madison Indian Reservation after 1880. These changes marked a significant transition to their traditional way of life and they faced many challenges. Determined to hold onto their ancestral ways, Puget Salish people continued to practice their religious ceremonies in secret, as they were outlawed for generations. Fishing and other harvesting continued to be central to their way of life. They still frequently came to Seattle to sell fish and clams, and to visit with people from other tribes who were camped along the waterfront. Here, (left to right) Doctor Peter, Charlie Yukton, Mary Jacob, Jacob Wahalchu, an unidentified person, and Mary Adams wait at the Colman Dock for the steamer to take them back across the water to the reservation after a day in the city in the early 1900s.

Description courtesy of the Suquamish Museum | suquamishmuseum.org

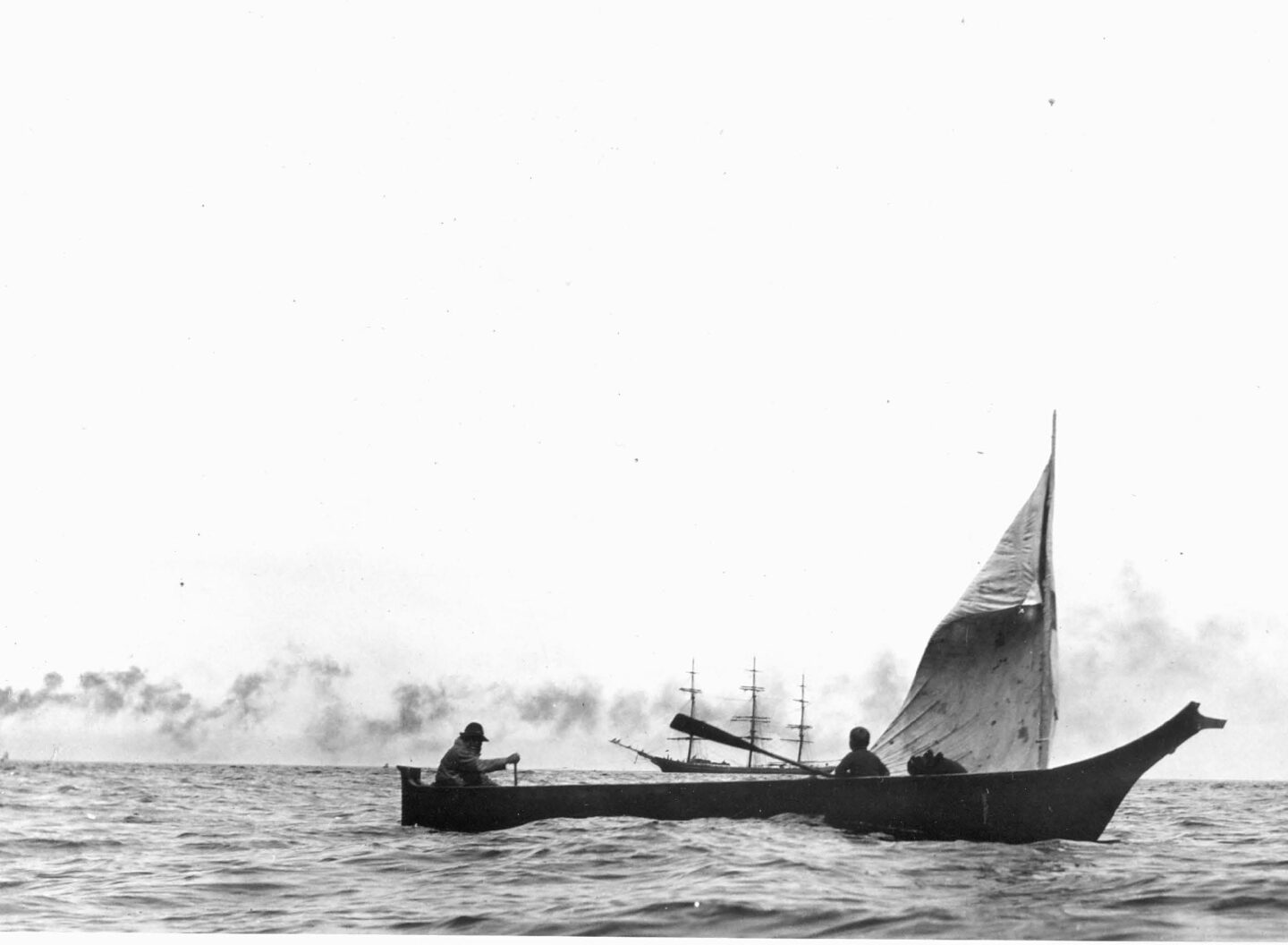

Lawrence Webster (1899-1991) of the Suquamish Tribe, recalled his childhood visits to Seattle in an oral history recorded in 1985:“They would sell fish and clams at fish markets in Seattle. I was very young; four or five, they would still take smoked salmon over to Seattle or Lake Washington and trade it with people from Yakama or Snoqualmie. They’d trade back and forth. They used to paddle across Elliott Bay in the big canoes and camp there a short way south of what is now known as Yesler Way. That was mostly mud flats down there, but there were a few pieces of high ground, and that’s where the Indians used to camp. Those big canoes were really seaworthy, even more so if they were loaded down. If it got rough, you could put up a small sail if you were going in the right direction. If you weren’t, you just found a place to pull in and camp until the blow was over.”

Description courtesy of the Suquamish Museum. suquamishmuseum.org